You are here

In France today, 1 to 2% of the population is directly affected by autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), a set of conditions that fall more broadly into the category of neurodevelopmental disabilities, which as a whole impacts one in six persons. In this context, a new national strategy for neurodevelopmental diseases was launched in France on 22 November, 2023, with the aim of improving and pooling research for a better understanding of ASDs, from their cause to their treatment. Coming after two decades of considerable progress in research, which has transformed the perception and representation of autism, the launch of this plan offers an opportunity to take stock of recent scientific advances concerning this condition.

(Re)defining autism

What exactly does the term “autism” mean? As mentioned above, it is a neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD). “NDDs, which affect the functioning of the brain, encompass all the conditions starting with ‘dys’ (dyslexia, dyspraxia, dysphasia), attention deficit with or without hyperactivity, intellectual disabilities and certain forms of epilepsy – an entire spectrum with varying degrees of severity,” explains Professor Caroline Demily, head of the Adis autism and intellectual disabilities unit at Le Vinatier Hospital near Lyon (southeastern France), and director of GenoPsy, a rare diseases reference centre for genetically-expressed psychiatric disorders. Concerning autism, she explains, “It is characterised by difficulties in communication and interaction, restricted interests and stereotypy . There can be a very wide range of expressions, depending for example on whether autism is associated with an intellectual disability or with camouflaging in the case of subjects with a high performance level and capacity for learning.”

While autism is now perceived with wider, more inclusive acceptance, as evidenced by the increasingly common use of the term “autism spectrum disorder”, this has not always been the case. Brigitte Chamak, a sociologist and scientific director of the “Vie Sociale des Neurosciences”1 project, explains that since the 1980s the criteria for diagnosing autism have been greatly expanded, accompanied by a kind of translation from psychiatry to neuropsychology: “With the creation of the pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) categories, autism – which was once considered a rare, severe and incurable disease – has become a syndrome that encompasses not only non-verbal subjects with severe communication problems but also individuals with cognitive and language abilities who have restricted interests and difficulties with social interactions.”

While the broadening of diagnostic criteria has logically led to more cases being identified and subsequently treated, it has also contributed to an invisibilisation, in both research and public policy, of autism sufferers with severe, non-verbal disorders and/or significant intellectual disabilities, Chamak points out.

Along with the changes in diagnosis criteria for autism disorders, new etiological perspectives have emerged. Psychoanalytic explanations attributing causal responsibility to the parents’ psychological makeup have been abandoned and many myths blaming vaccines, gluten intolerance, etc., have been debunked, in parallel with important discoveries in genetics and neuroscience. “Rather than a relational disorder, autism is now considered to be linked to a cerebral dysfunction,” reports the neuropsychologist Sylvie Chokron, a CNRS research professor and head of the vision and cognition unit of the Paris-based Rothschild ophthalmological foundation.

From genetic diagnosis to treatment

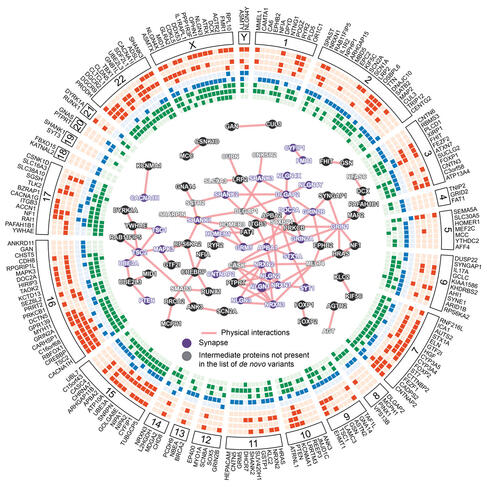

Professor Thomas Bourgeron, a geneticist at Institut Pasteur’s Human Genetics and Cognitive Functions laboratory2, explains the heritability of autism disorders: “Analyses of twins and families show that genetics makes a very important contribution to autism. The first genes were identified in 2003, revealing the existence of monogenic forms: a single mutated gene, or even a single copy of the mutated gene, can cause autism, an intellectual disability or a total lack of spoken language. In some cases there is also a main gene that is responsible for less severe forms in subjects who are highly articulate and have normal or even high IQs.”

Bourgeron also underlines the changing nature of the influence of genetic mutations: “Some variations lead almost inevitably to a diagnosis of autism, whereas for others, fewer cases are identified – either because the subjects are not autistic, have not had access to diagnosis, or because the symptoms are less tangible. It’s rather like an opera orchestra: if the lead soprano stops singing it is immediately noticeable. But if the fifth violin stops playing it’s much less perceptible. However, if several violins drop out at the same time, it makes a real difference. Not all genetic variations have the same consequences. Some will have a strong impact, while others, more frequently found in the population, will have a subtler effect. It is their accumulation that increases the likelihood of an autism diagnosis.”

“Most monogenic forms of autism correspond to forms with intellectual disability,” the geneticist adds. “Today, when the subjects’ and their parents’ complete genomes are mapped, a known genetic origin is found in 30 to 40% of the cases with intellectual disability. It is estimated that there are about 1,700 genes strongly involved in neurodevelopment, including just over 200 that, when mutated, result in a high probability of autism.”

The polygenic forms, on the other hand, correspond to more frequent variations in the population and are responsible for less severe ASDs, without intellectual impairment: “To extend the orchestra analogy,” Bourgeron adds, “these variants are like the violinists, each one playing a small part of the score, and together producing a musical performance.”

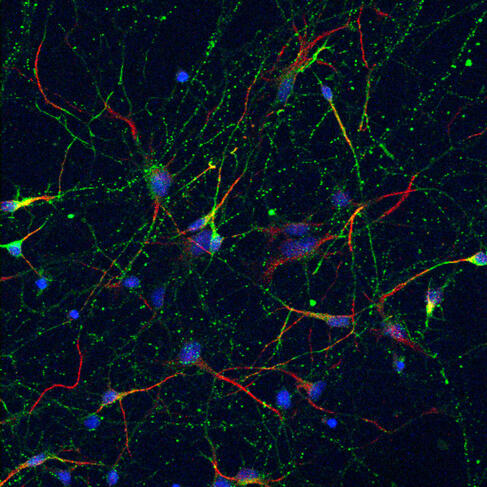

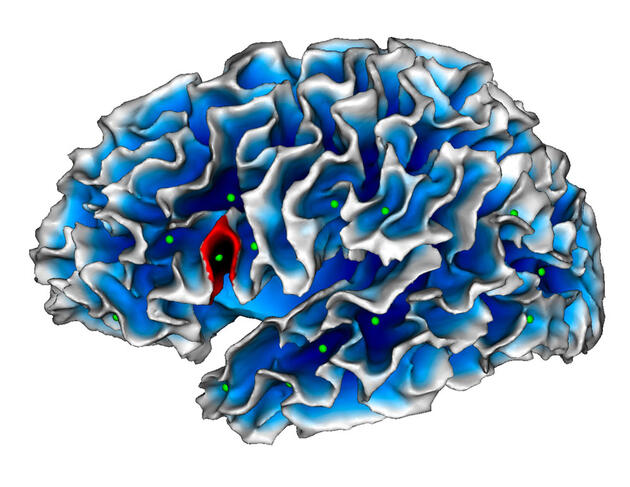

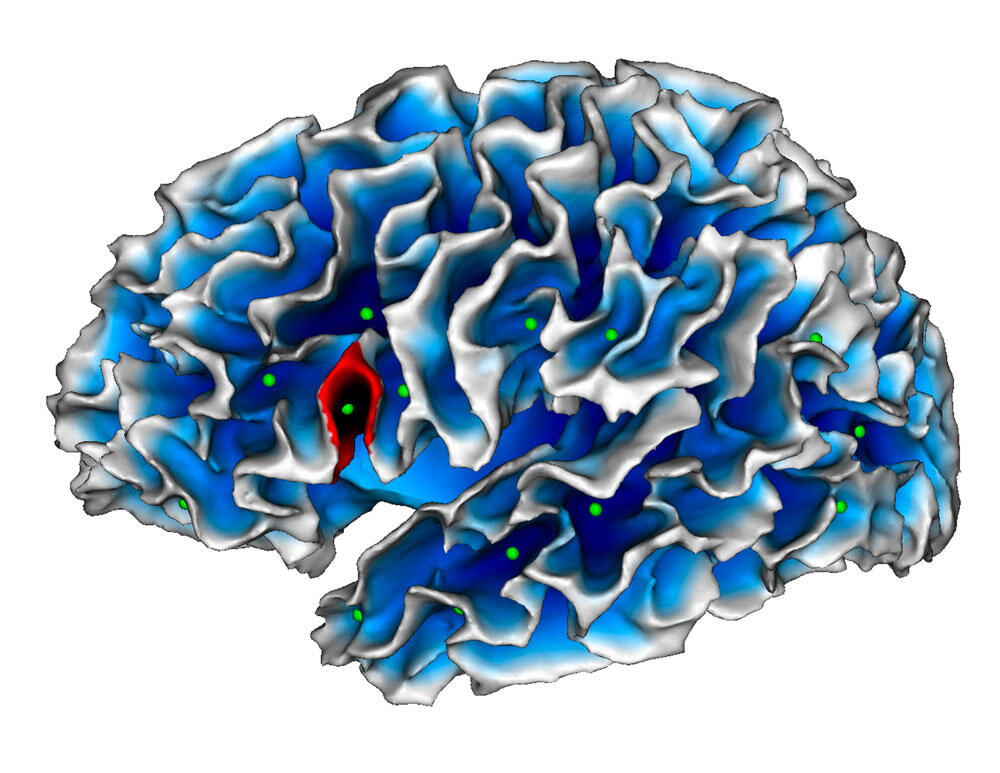

These genetic mutations give rise to singularities in the brains of autistic subjects, as the geneticist explains: “The biological role of the genes involved in the functioning of the synapses, the connections between neurons, is now better understood. In some cases, depending on the person, there are slightly fewer or more synapses – in other words, a little more or a little less connectivity between neurons.” These particularities could explain the differing manifestations of ASD, such as difficulty adapting to changes of routine or environment, and/or hyper- or hyposensitivity (to sounds, light, odours, flavours, etc.).

Far from being purely descriptive, these discoveries regarding the genetic aspect of autism also open up new therapeutic possibilities. “The genetic diagnosis of autism is no longer a silent observation. We are now able to offer personalised treatment strategies,” says Demily, who points out that understanding the genetic factors behind autism has paved the way for an approach based on individual genetic diagnosis: “In some cases, this diagnosis can lead to customised therapeutic adaptations. For example, people suffering from Smith-Magenis syndrome, a genetic disorder caused by a microdeletion of chromosome 17, benefit from a prescription of beta blockers to inhibit melatonin secretion during the day, followed by melatonin at night. This restores the sleep-wake cycle, allowing sufferers to function more normally and lead fulfilling social and professional lives. For other syndromes, different therapies are available. In short, genetic diagnosis is now beginning to change our treatment approaches.”

Bourgeron cites another example: “Genetic identification also makes it possible to detect a metabolic disease that causes an autistic presentation, such as phenylketonuria, which triggers the accumulation in the organism of phenylalanine, an amino acid that inhibits brain development in children, resulting in an intellectual disability. It’s now possible to modify the children’s diets so they do not suffer from intellectual impairment.”

The geneticist reports that clinical studies are underway to evaluate the effectiveness of lithium on subjects who have a mutation of the Shank3 gene. “I think that in certain cases of autism with intellectual disability and/or epileptic seizures, some forms of gene therapy will be possible in the future,” he says. “But the brain is a very complex organ, and much more research will be needed to develop such therapies.”

Intertwining sensorineural causes

Improved understanding of the genetic origins of autism – or rather certain forms of autism – should not deflect attention from the other possible causes of these disorders. “The majority of autistic subjects probably do not have a genetic abnormality, but a neurodevelopmental impairment linked to harmful neurological events at the time of their birth,” Chokron emphasises. “The neurological factors that predispose to autism are the same as those that may lead to other neurodevelopmental problems.” The neuropsychologist laments “the tendency to talk about comorbidities in connection with complex neurological disorders that might possibly all arise from the effects of a single harmful process”.

Factors that may be responsible for an ASD as well as other NDDs include prematurity, certain medications like Depakin taken during pregnancy, viral infection and neuro-inflammation. This often results in the intertwining of various symptoms with overlapping diagnoses. For example, 50% of autistic subjects are affected by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and 30% of ADHD sufferers are also autistic.

For Chokron, this raises certain methodological problems: “Studies intended to describe autistic persons often commit a methodological error by making comparisons only with neurotypical subjects and not with those who live with other disorders, in particular neurodevelopmental. As a result it’s hard to discern what is really an effect of autism and what is caused by other conditions.”

Based on her experience as a specialist in neurovisual dysfunctions, Chokron offers an illustration of this etiological and diagnostic complexity: “Neurovisual disorders, like the inability to follow an object with the eyes, may lead to an autism presentation. These disorders can in fact hinder a child from interacting with the outside world and the parents might interpret this discomfort as a symptom of autism. In actual fact, this clinical presentation mimicking autism is the direct consequence of a neurovisual impairment, and not all children concerned are autistic. We have realised that there are environmental and educational factors that protect against interaction disorders.” she says. “At the same time, autistic subjects often have visual issues that resemble those of non-autistic individuals with neurovisual disorders. We have been able to demonstrate that there is little difference between the two in visual terms.”

All of these reasons have led the scientist to investigate “primary” etiological factors that, in her opinion, have not been sufficiently explored: “For a long time it was taken for granted that autistic persons see and hear ‘normally’, but we may have overlooked some rather fundamental factors, especially since autistic children are difficult to examine, and because the focus is often placed solely on visual or auditory acuity rather than central cerebral aspects. Fundamental disorders can interfere with social interactions and predispose to dysfunctions. In fact, any sensory condition can cause interaction problems. For example, we know that there are 40 times more cases of autism among visually impaired children than in the overall population.”

Improving autism diagnosis and coaching

All of this research, whether in the field of genetics or neuropsychology, is faced with a double challenge: to improve the quality of ASD diagnosis by limiting variances resulting from quasi-similar symptomatological presentations, and to strengthen and optimise autism coaching. Regarding the quality of diagnosis, Demily stresses the importance of communication: “Even though autism has long been caricatured as specific to childhood, it lasts through the entire lifetime, and psychiatrists must be better trained to take this into account. More training is also very important for general practitioners, who are on the front line, as well as paramedical and social professionals: psychologists, speech therapists, occupational therapists, etc.” Concerning this point, it should be noted that France’s new national strategy for neurodevelopmental conditions specifies that all children’s health records must include a 20-page questionnaire enabling physicians to screen for possible neurodevelopmental disorders, with the goal of offering earlier detection and coaching on a wide scale.

Regarding therapeutic procedures, in addition to approaches based on medications addressing a possible genetic cause, the emphasis is now on educational, cognitive-behavioural and developmental strategies conceived to help autism sufferers compensate for their difficulties, manage certain conditions and potentiate their abilities. It is important to note that discussions on these procedures are underway at various levels. Chokron warns against methodological shortcomings that might make these solutions ill-adapted to the needs of non-verbal autistic patients and/or those with significant intellectual impairment: “To conduct a behavioural study, the subjects must be able to understand and carry out a task. That necessarily excludes autistic persons who are non-verbal or who have severe intellectual disabilities. Most often, the test subjects have a good (or subnormal) intellectual level. Consequently, we don’t know how much of a gap there is between the test subjects’ functioning and that of more severe cases.”

In addition, today’s research is also exploring ways to improve the social inclusion of people with autism, especially in the urban environment. As Demily explains, “There’s a new approach in neuro-architecture research that consists in creating spaces designed for the particularities of autism, with more soothing perspectives, alcoves, modularity, more subdued lighting, easier circulation, etc. A unit built in collaboration with architects, caregivers and other actors involved in autism will open in 2024 at Le Vinatier Hospital. We’re also working on the development of an application called ‘Divercity’ that patients will be able to use to geolocate themselves and find places in the city (shops, bars, restaurants…) with autism-friendly facilities.”

The next step will no doubt be the promotion of the concept of neurodiversity, which, as Chamak puts it, “celebrates the diversity of ways of thinking” and “demedicalises” a condition that was once considered pathological in order to achieve better integration. ♦

Comments

Log in, join the CNRS News community